Years in office: 1865-1869

Years in office: 1865-1869Pre-service occupations: military governor of Tennessee, senator, vice president

Key events during his administration: presidential Reconstruction (1865-1866), military Reconstruction begins (1866), impeachment (1868), purchase of Alaska (1867), 13th Amendment (1865), 14th Amendment ratified by Congress (proposed 1866, ratified 1868), Nebraska admitted to the Union (1867); Hancock’s War (1867); Washita battle/massacre 1867; Fetterman massacre (1866)

Presidential rating: Near failure and mostly unpopular

ESSAY

To modern Americans, Andrew Johnson was the answer to a trivia question—up until 1998, that is: who was the only president to have been impeached. He was also the first man to succeed an assassinated president, the only Southern Senator who refused to join the Confederacy, and the first president to have a veto overturned.

Andrew Johnson was never meant to become president—at least, not by Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans. He was an “olive branch” candidate, a Democrat joined with Lincoln to form a unified ticket against the McClellan/Copperhead Democrats in 1864.

But Lincoln’s shocking murder propelled Johnson to the presidency, something that neither he expected nor the Radical Republicans thought would happen. What followed were four torturous years between an unpopular president, an over-reaching Congress, and a blasted South ripped between newly freed slaves and ex-rebels.

Before starting this evaluation of Johnson, my primary view of him was that, for all of his faults, he performed one service that every president following him owes a debt of thanks: he fought an imperial Congress trying to impeach him over an unconstitutional law—and won. I wanted to see if that view holds up against the historical record.

The view not only holds up, but Johnson did other things that merit praise from history, which I’ll discuss in detail. However, his record is quite mixed. Understanding him must involve more than reducing the 17th president to a one-dimensional caricature of a backwards, barely literate racist. He deserves better. Much better.

That’s not to say I agree with everything Johnson did while in office—far from it. He was a disagreeable man who sought to create a new postwar party, with himself at the center. His actions were motivated by the desire for power as much as they were by the desires to maintain white supremacy and beat down the new “traitors,” the Radicals.

Andrew Johnson was often wrong in his motives—and his racism is sometimes hard to stomach—but he was often right in his actions.

A man of the people

He had been born in poverty in North Carolina—returning there as president was a special treat—and moved to Tennessee in his youth. It’s safe to say that no other president has experienced as much of a rags-to-riches life as had Andrew Johnson. He was orphaned when he was three. He learned the craft of a tailor and would often be referred as one in his political career. Johnson never attended school; his wife, Eliza, taught him basic reading and writing skills.

Some presidents built their political power based on their party organizational skills (Martin Van Buren, Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson); some men did so based on good political acumen (Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, Bill Clinton); others have done so as a sheer cult of personality (George Washington, William Henry Harrison, Dwight Eisenhower, Ulysses S. Grant). Others are a combination of one or more of the above (Franklin Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan). Andrew Johnson built his political power based largely on the power of his mouth.

Picturing Andrew Johnson as a “man of the people” may seem odd, but that’s what he was. Johnson came of political age in Tennessee, where stump speaking was far more important than newspapers. Johnson was a master of oratory, which could sway opinion often better than the highly partisan press could, if used in the right places. His powerful speeches made him Tennessee’s golden boy in the 1850s. His style was quite aggressive, and he would directly engage the audience; this served him well in Tennessee, but would help destroy him as president.

Having been born quite poor, Johnson’s frequent targets were men of privilege, especially the planter class. Johnson was no abolitionist—he was about as far from being one as you could get—but he despised the planters.

He rose through Tennessee politics, clawing (possibly the best word) his way from alderman, to state legislator to governor to finally U.S. senator.

Pro-war/pro-Union Democrat

During the secession crisis, Andrew Johnson declared he would remain loyal to the Union. He powerfully denounced the “traitors” of the South and toured Tennessee urging against secession. When Tennessee went with the Confederacy, Johnson became the only Southern senator to remain with the North, earning him much hatred in the South and much praise in the North.

In 1862, he left the Senate to become military governor of Tennessee, where he proved quite effective in helping quash the rebellion. Eastern Tennessee was of course pro-Union; the western half of the state was Confederate country. By early 1864, the state was permanently in Union hands except for Hood’s expedition late in the year.

Johnson apparently freed his own slaves in 1863. No friend of blacks—he favored shipping all of them back to Africa or at least an America without them at all—Johnson nevertheless embraced the Lincoln administration’s emancipation policy in 1863. He argued that slavery had brought on the war and it needed to be destroyed.

This move at once set him apart from Northern Democrats and furthered his alliance with the Republicans. Embracing emancipation made re-establishing civil government in Tennessee more difficult for Johnson, who had enough troubles through using often high-handed measures. Although he kept Nashville in Union hands after its fall in 1862, he was unable to fully reorganize the state. In 1864, he attempted to require a loyalty oath from both pro-Union and pro-rebel citizens, which naturally outraged Unionists, and called a state convention. But his efforts failed. Biographer Hans L. Trefousse explains that:

(Johnson’s) ambition for higher office made him careless. He achieved his personal goal [becoming vice president], but his administration of the state suffered. For a time, however, his great popularity in the North caused admirers to overlook his shortcomings. These would not become evident until later. (Trefousse, p.175)

Because of Johnson’s status as a committed pro-Union Democrat who supported the administration’s goals and the uncertainty of the 1864 election, Lincoln tapped Johnson to be his vice president under the banner of the National Union Party (the temporary name of the Republican Party). He seemed the ideal choice.

At the inaugural, though, it seemed like a terrible mistake had been made. Johnson had been sick with typhoid and to brace himself for his speech, he took a couple of shots of whiskey. He speech was a rambling and slurred affair, embarrassed Lincoln (and Johnson, of course) and immediately tagged Johnson as “the drunken tailor.” Even though Johnson’s explanation is acceptable, he never lived it down.

The “Avenger” and securing the war’s end

Vice President Johnson escaped the Booth conspiracy that assassinated Lincoln and wounded Secretary of State William Seward when his own would-be assassin chickened out. A stun

ned Johnson became president on April 15.

ned Johnson became president on April 15.He assumed the presidency while the war was still underway—Lee had surrendered, but several Confederate armies remained in the field, most notably Joe Johnston’s in North Carolina, facing William T. Sherman. Cries arose from the North for vengeance against the South for Lincoln’s murder, but throughout the rest of April and into May 1865, Andrew Johnson acted in a way that deserves much praise.

He saw to it that vengeance did not rule the day, but that the war ended on the right terms.

The most alarming development came when the president received the surrender terms that Sherman had given to Johnston in North Carolina. In effect, Sherman’s terms were so generous that the Confederate state governments would remain in power and the results of the war would be all but negated! In his defense, Sherman knew they would probably be rejected—and unlike Lee’s army at Appomattox, Johnston’s army was not surrounded and was still free to maneuver and fight—and he was right. Johnson ordered hostilities resumed until terms similar to the ones Grant gave Lee were worked out. (Secretary of War Stanton added a personal insult to the orders, which created permanent hostility between the men.) This was done, and Johnston surrendered.

By the end of May, all Confederate armies were surrendered and Jefferson Davis had been captured. Johnson ordered him placed in irons in Fortress Monroe, which outraged some but pleased the Radicals, who recalled Johnson saying early in the year that Davis should be hanged.

By maintaining a cool head in the wake of Lincoln’s murder, Sherman’s outrageous terms to Johnston and the final details of the war—and in keeping with Lincoln’s desire to end the war on the “let ‘em up easy” terms that Grant gave Lee—President Johnson brought the war to an end. It’s no easy feat, when you consider that some rebel leaders were countenancing continuing the fight through guerrilla warfare and some Northerners wanted to renew all-out war because of Lincoln’s death.

Johnson’s zenith

When Andrew Johnson became president, most people didn’t know exactly what to expect: the “drunken tailor”? Davis’ hangman? A new Lincoln? A new “Moses” for the newly freed slaves? None was right. Johnson knew that the first thing he was expected to do following the c

onclusion of the war would be to continue and expand the reconstruction of the South.

onclusion of the war would be to continue and expand the reconstruction of the South.He retained Lincoln’s cabinet, of whom the most important members were Stanton at War, Seward at State, Gideon Welles at Navy and Hugh McCullough at Treasury. All four men were highly capable. Welles and Seward were the most loyal to Johnson, and consequently for Seward, it meant the end of his political career. Johnson sometimes questioned McCullough’s loyalty but never his ability. But Stanton and Johnson were enemies, and Johnson’s failure to remove him early on when he had the chance would help trigger his impeachment.

But that was in the future, and in 1865, Johnson enjoyed the greatest popularity of his life. Praise for him was near universal, especially following the introduction of his reconstruction program, leaving one historian to remark that if he had died in early 1866, he would be remembered as one of the greats.

Here was the situation, then, in the summer of 1865: 10 states were to be “reconstructed” for their formal re-admittance to the Union: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas and Texas. (Louisiana had already been readmitted under Lincoln’s 10% plan.)

During the summer of 1865, Johnson introduced his reconstruction program. Latter-day historians have fount fault with this, but historian Albert Castle correctly points out that 1) the people expected Johnson to act, having gotten used to strong executive action under Lincoln; and 2), not acting would make him appear weak and indecisive—of which he was neither. His plan, though, differed in a way from Lincoln’s 10% plan, where loyal Unionists could return a state to the Union with full representation as long as the state government was reorganized by 10 percent of those who had been eligible to vote in 1860. It wasn’t a perfect plan, but it was designed to “let ‘em up easy,” in Lincoln’s words, and return the Southern states quickly to the Union.

Where Johnson’s plan differed was this: At first, he seemed to favor harsh reprisals against all senior civil and military leaders in the South, as well as all planters, and reorganize land and power in the hands of the men who were “mislead” by the secessionists. But Johnson decided that to exact revenge against the hated upper class would leave the Southern states vulnerable to Radical designs on the South, most notably black suffrage. Black suffrage most likely meant loss of white influence and increase of Radical power (Johnson would soon consider all Republicans as “Radicals”). So, to thwart the possibility of black suffrage, Johnson started issuing presidential pardons to practically any ex-Confederate who called for one—except for the highest-ranking ex-rebels, that is.

The idea was to return the states to the Union quickly without the need for black suffrage—and to counter Republican protests, Johnson quite rightly pointed out the hypocrisy of imposing the franchise on the Southern states when it was denied in the “free” North. In short, Andrew Johnson did not believe in Reconstruction per say because he did not see the need for it. As with Lincoln, he never recognized the legal right of secession; so, the Southern states never left the Union. Therefore, the states didn’t need to be “reconstructed,” but needed to be readmitted quickly with legal governments.

The idea was to return the states to the Union quickly without the need for black suffrage—and to counter Republican protests, Johnson quite rightly pointed out the hypocrisy of imposing the franchise on the Southern states when it was denied in the “free” North. In short, Andrew Johnson did not believe in Reconstruction per say because he did not see the need for it. As with Lincoln, he never recognized the legal right of secession; so, the Southern states never left the Union. Therefore, the states didn’t need to be “reconstructed,” but needed to be readmitted quickly with legal governments.Johnson’s pardons let ex-rebels lead the way in re-organizing their states, so that by year’s end, they had elected new members to Congress—many of them ex-rebels, and even a few of them attempting to reclaim their pre-war seats.

It was the first break between Johnson and the Republicans, but in this summer and fall of Johnson’s glory, the cracks were tiny.

Johnson’s pardons and dreams of party

Perhaps nothing better illustrates the seemingly contradictory nature of Andrew Johnson than his presidential pardons. Throughout the secession crisis and war, h had strongly battled and denounced the “traitors” in the South, especially the planters. But during the summer, he started issuing pardons as if they were party favors. Why the switch? The best explanation, writes Castle, is his desire to be a party-builder:

By summer it was clear that the Confederate leadership retained the allegiance of the Southern masses … At the same time, it became evident that in most parts of the South the Unionists were few in number and low in ability. …Thus Johnson must have realized that whether he liked it or not, he would have to work through and with the followers of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee if he were to bring the South back into the Union and keep himself in the White House.He would have to pardon many Confederates, let them take offices and restore normal government, thereby fostering a new loyalty to the Union and alliance with their Northern Democratic brethren—with Johnson at the head. Johnson wanted to fashion a new party of Democrats and conservative Republicans: a new coalition that depended on rapid restoration in the South. But the Radicals had other ideas. So, the “traitors” became his hope for staying in power, and his allies, the Republicans, would become the new “traitors,” and their programs to refashion the South to their liking threatened Johnson’s ambition.

Throw into this mix the Republicans’ own ambition, Johnson;’ belief that his course was correct, sincere Radical Republican steps toward racial equality and increasing hostility between the president and Congress, and you have the mix for an explosive situation.

Opposition to presidential Reconstruction

The South was blasted: the economy was ruined; thousands of farms destroyed; railroads wrecked; Richmond, Atlanta, Columbia, SC and Jackson, Miss., were destroyed, as well as numerous other small towns; and the social order had completely broken down.

In his masterpiece Reconstruction, Eric Foner describes how the simple fact of being able to go where one pleased caused probably half of all ex-slaves to be on the road. Quite often, they were looking for family members separated on the auction block. Whites saw this and misinterpreted it as being what they had long feared: lazy blacks unable to account for themselves without directions from their betters. There’s more to it than that, of course, as there was crime both black on white and white on black, but by the end of 1865 came the first of many “Black Codes” in the South.

These odious rules were designed to put blacks “in their place” and were

a slide back toward slavery. Dismayed Republicans, who controlled Congress, refused to seat the delegates from the Southern states while these outrages were committed against blacks. (Federal organizations such as the Freedman’s Bureau, which had been created to help with the transition from slavery to freedom, were largely ineffectual.) The codes did give blacks some rights, but they relegated them to second-class status.

a slide back toward slavery. Dismayed Republicans, who controlled Congress, refused to seat the delegates from the Southern states while these outrages were committed against blacks. (Federal organizations such as the Freedman’s Bureau, which had been created to help with the transition from slavery to freedom, were largely ineffectual.) The codes did give blacks some rights, but they relegated them to second-class status.The refusal to seat the Southern members angered President Johnson. Now, to his credit, Johnson was not happy with the actions of Southerners who abused the goodwill of his pardons, and instead of “repenting” and treating the newly freed slaves well, they mistreated blacks and elected “unrepentant” rebels to Congress. He only had himself to blame for that, however, through his quite lenient pardons policy. Johnson also misunderstood why he was popular, overestimated the popularity of his own policy and also underestimated the determination of the Republicans to preserve their power and postwar vision.

Radicals, lead by Thad Stevens in the House and Charles Sumner and Ben Wade in the Senate, had opposed Lincoln’s 10% program, and sought harsher measures against the South. Initially, they supported Johnson’s program, but started to turn against him over the pardons, and realized that Johnson would be a dangerous opponent if his policies continued. Thus they refused to seat the Southern delegates because of the Black Codes and the fact that allowing “unrepentant” ex-rebels to return to the government was tantamount to abrogating the reasons for the war.

Johnson said differently in his first message to Congress that December. His message was well received by all except the Radicals, and marked them, so Johnson hoped, as the party of division and disunion. He confidently believed Northerners would side with him over Radicals who were pushing for black rights.

The winter of 1865-66 marked the height of Johnson’ popularity. But the Radicals were only just getting organized. Letting the defeated South back into the Union with blacks in a condition almost like slavery was unacceptable—almost as if the war hadn’t happened.

So why did Johnson fail?

Battling Congress and blunders

Andrew Johnson believed that once the Southern delegates wee seated, Reconstruction was finished. He thought wrongly. As Castle explains, acceptance of Johnson’s presidential Reconstruction by the North was contingent upon it actually working. If it didn’t—and the treatment of the ex-slaves and the unrepentant attitude of Southerners made it clear that it wasn’t—Northerners expected Johnson to work with Congress to try something different.

Johnson was a stubborn man for which defeat only energized him that much more. He believed correctly that the North no more wanted black equality than did the South, but he misread the Northern desire for black rights, at least in the South—and that Northern belief was based on perceptions of how horrible whites treated blacks there (which was not too different from the North) and the fact that most Northerners correctly believed that they wanted the South to accept the results of the war for which 300,000 Northerners had died. So Johnson was both right and wrong, and he underestimated Northern opinion in the fight to come.

Johnson was a stubborn man for which defeat only energized him that much more. He believed correctly that the North no more wanted black equality than did the South, but he misread the Northern desire for black rights, at least in the South—and that Northern belief was based on perceptions of how horrible whites treated blacks there (which was not too different from the North) and the fact that most Northerners correctly believed that they wanted the South to accept the results of the war for which 300,000 Northerners had died. So Johnson was both right and wrong, and he underestimated Northern opinion in the fight to come.The first showdown came with the re-authorization of the Freedman’ Bureau in early 1866, which Johnson determined to veto as both unnecessary and unconstitutional, as it placed military over civilians in peacetime, extended rights to blacks denied to whites, etc. The public at large hailed his veto message, and his veto was barely sustained. Again, Johnson seemed to be master of the situation and of Congress.

Then Johnson tripped—over his own tongue.

On Washington’s birthday, Johnson spoke to a crowd of well-wishers, despite the advice and warning of cabinet members He said the old traitors had been defeated, but new traitors had appeared in the North. Worse, at the urging of the crowd, he named them by giving names of prominent members of Congress. He also compared his sacrifices for the country as those of Jesus Christ, and his policy henceforth would also be on of forgiveness (unlike the Radicals). The crowd loved it, of course, but the North was not amused:

The vast majority of Northerners felt outraged or shamed [over] Johnson’s speech. In their eyes he had disgraced himself and the presidency. Many of them suspected—or concluded—that he had been drunk again. In particular, they resented his denunciation of Stevens and Sumner; whatever else they might be, the two were not traitors to the Union. Indeed, Johnson’s attack on them enhanced the prestige of both the Radical leaders, with Sumner probably being saved from defeat in his bid from re-election to the Senate. Even Johnson’s friends ex-pressed regret over his performance. … All in all, Johnson had committed an act of great personal and political folly. (Castle, p.70)Johnson’s aggressive stump speaking that had served him so well in Tennessee before the war was obviously a liability on the national stage. By attempting to prove that he was master of postwar America, the president instead hurt himself. And it was only going to get worse.

When the Republican Congress passed a civil rights bill in early spring, Johnson could have rescued his respect and reputation by signing it, but he vetoed it on the grounds that it favored the colored over the white. His contemporaries and most historians of all eras agree that it was a huge blunder, because it “turned friends into enemies, united Moderates and Radicals, and made the issue between him and Congress not the Negroes’ political rights, on which he probably could have won, but their civil rights, on which he was doomed to lose.” (Castle, p.71, emphasis added)

Johnson didn’t realize it yet, but he also dashed his chances for the presidency. But why did h do it? Most likely because he believed his reconstruction program was sufficient—and no more was needed—coupled with his racism, growing disgust with the Radicals over their hypocrisy (forcing black suffrage on the South when thy wouldn’t do it in the North) and his own political ambitions, which required Southern Democrats.

But Johnson was about to learn that the Radicals were not the same enemy as the “traitors” of the South; and indeed, he was his own worst enemy.

The Radicals fight back; the disastrous “swing around the circle”

In the spring of 1866, Congress and the president engaged in a tragic-comedy of dueling Reconstruction programs. While Congress was overriding Johnson’s civil rights bill veto, Johnson issued a proclamation declaring that the rebellion was at an end and Southern states restored to the Union. He also declared an end to military tribunals in the South.

Congress disagreed, and continued to deny the Southern delegations their seats. In response, Congress created the 14th Amendment to the Constitution: its own peace terms with the South, and the cementing of certain civil rights legislation in the Constitution. This in effect made all blacks U.S. citizens who would enjoy the full protections of the federal government. If the vote were denied to male inhabitants of a state (e.g., blacks), that state’s representation in Congress would be proportionately reduced. (See the full text here.)

This was actually a Moderate Republican measure, not a Radical one, and people hoped the president would acquiesce. But Johnson and the South treated it as a gross affront. Even though the executive branch has no legal role in amending the Constitution, Johnson fought the 14th Amendment. He claimed that the current Congress had no authority to amend the Constitution while it unconstitutionally prevented duly elected members from assuming their seats. Here was another instance where Johnson was both correct and wrong: correct in that the 14th Amendment—though right in its language—is nevertheless very questionable in how it was passed, and wrong in that the executive has no say in who Congress admits into its halls.

The Radicals promptly seated some Southern members—Republicans, that is, including Johnson son-in-law. Angered, Johnson decided to retake the argument and his prestige thro

ugh an unprecedented move: he would go on tour and argue his case in person.

ugh an unprecedented move: he would go on tour and argue his case in person.Using the dedication of a monument to Stephen A. Douglas as a catalyst, President Johnson undertook the first “whistle stop” campaign in American history during the summer of 1866. The president dragged Gen. Grant and cabinet members along with him, but Grant would later abandon Johnson when it became clear that the president was just using the “hero of Appomattox,” making it seem like Grant was in agreement with the president’ Reconstruction policies, when in actuality, he wasn’t. The so-called “swing around the circle” to New York, then west to Chicago, then St. Louis and back to Washington, was intended to be a triumph. Instead, it was a disaster.

It started well enough, but in Cleveland, Johnson again ignored the advice of Seward, Welles and other confidants to hold his tongue. Craving the attention and to make his case, he made an unprepared speech before a crowd outside his hotel. In response to hecklers, he became increasingly aggressive and, to put it kindly, unhinged. The exchange got nasty and culminated with Johnson demanding,

"The twelve apostles had a Christ and he never could have had a Judas unless he had the twelve apostles. If I have played the Judas, who has been the Christ that I have played the Judas with? Was it [abolitionist] Wendell Phillips? Was it Thad Stevens? Was it Charles Sumner?”Stops at St. Louis and elsewhere were little different, and Republican newspapers and even some Democratic ones pounced on Johnson’s incredible demagoguery. He hurt himself badly with the “swing around the circle.”

At this point, the cry came, “Why not hang Thad Stevens and Wendell Phillips?”

“Yes,” said Johnson, “Why not hang them?” (Castle, p.92)

His reputation was ruined in the North among both Republicans and Democrats, who had rejected him at a “National Union Movement” convention earlier in the summer.

In the fall elections, Republicans increased their power throughout the North, reversing the Democratic gains of 1864—and it was all largely because of Johnson and his mouth. It was also because he believed that the duty of the government was the restoration of the Union, and not the imposition of black rights on the South that Republicans were denying to them in the North.

Military Reconstruction and the veto wars

Andrew Johnson bears the ignominy of being the first president to have a veto overridden (the aforementioned civil rights bill of 1866). It wouldn’t be the last. Congress overrode single veto Johnson made, which speaks to the president’s inability to build effective coalitions in Congress, his unpopularity and the Radicals’ power—and pettiness.

By the end of 1866, all of the Southern states, with governments comprised of ex-Confederates in power thanks to Johnson’s lenient pardons, had rejected the 14th Amendment. Because of that, and outrages committed against blacks and Unionists, the Radicals used their newfound majority strength to create a new Reconstruction program: military Reconstruction, whereby the South was divided into five military districts ruled by a general appointed by the president (and approved by Congress, of course). The general would have total authority in his states, and the present state governments would be abolished and high-ranking ex-rebels would be disenfranchised. Blacks would get the franchise and so would those declaring loyalty. Readmission to the Union would be contingent upon acceptance of the 14th Amendment.

Enough Moderates agreed with the approach to create the First Military Reconstruction Act, which would have several more acts join it. President Johnson decried military Reconstruction as unconstitutional and despotic, and he was largely on solid ground. The Supreme Court had recently ruled in the Mulligan case that civilian trials by military tribunal were unconstitutional.

Johnson failed to convince Congress, of course, and both houses easily overrode his veto—which became a routine dance in Washington. Congress would pass a law, Johnson’s advisers would urge Johnson to sign it or pocket veto it lest the Radicals pass something worse, Johnson would veto it with a combination of solid constitutional arguments and racist appeals, and Congress would ignore him by easily overriding his vetoes.

Johnson failed to convince Congress, of course, and both houses easily overrode his veto—which became a routine dance in Washington. Congress would pass a law, Johnson’s advisers would urge Johnson to sign it or pocket veto it lest the Radicals pass something worse, Johnson would veto it with a combination of solid constitutional arguments and racist appeals, and Congress would ignore him by easily overriding his vetoes.Johnson was more correct than not in his arguments that the Radical actions in the South were unconstitutional, but his stubbornness, desire for greater power and labeling of the Radicals as the new traitors worked against him. Likewise, the Radicals stopped cooperating with Johnson in any way and put forth legislation both designed to strengthen their power (black votes = more Republicans) and do justice to blacks and Unionists in the South. The Republicans did respond to Johnson’s charge of hypocrisy in the North by placing black suffrage on state ballots, but they were defeated everywhere—and cost Republicans support. Only Johnson’s bad stumbles kept the Republicans from losing too much from those defeats.

The road to impeachment

That’s not to say Congress wasn’t exasperated with Andrew Johnson. Radicals bega

n looking for some way to impeach Johnson as early as 1866. Johnson was a roadblock to Northern desires to form a “more perfect Union.” The president and “unrepentant” white Southerners stood in the way.

n looking for some way to impeach Johnson as early as 1866. Johnson was a roadblock to Northern desires to form a “more perfect Union.” The president and “unrepentant” white Southerners stood in the way.Articles of impeachment were introduced, but nothing stuck until finally, a showdown cam over an act of Congress that was blatantly unconstitutional. To thwart Johnson and make sure he wouldn’t mess with Military Reconstruction, Congress passed (over Johnson’s veto, of course) the Tenure of Office Act in March 1867. It stated that the president could not remove anyone from office that he had appointed and that the Senate had confirmed unless the Senate approved the removal. Johnson rightly declared it unconstitutional because the Senate only provides advice and consent on the appointment, not removal, of executive officers, and eventually the Supreme Court agreed—but not until 1926.

Nevertheless, Congress made the law both to prevent Johnson from arbitrarily removing harsh generals from the Southern districts and, specifically, to prevent him from firing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Stanton, an old-line Democrat, had become a strong intimate of Lincoln’s during the war and was now thoroughly on the side of the Radicals. Johnson should have fired him when he had the chance—in fact he had more than enough good cause to fire him—but he had kept him on when he thought h could still use Stanton during his dreams of party-building. Now he was stuck with a man who was openly hostile to him and his policies, and Congress was determined to keep it that way.

Johnson decided he would test the law. He sought General-in-chief Grant’s cooperation in a scheme to suspend Stanton and elevate Grant to interim secretary of war. After an unhappy time, Grant stepped away, letting a triumphant Stanton return. Johnson still attempted to use Grant and also Sherman to get rid of Stanton—and he even succeeded in publicly humiliating Grant, who by this time was emerging as the likely Republican candidate for president in 1868.

Johnson decided he would test the law. He sought General-in-chief Grant’s cooperation in a scheme to suspend Stanton and elevate Grant to interim secretary of war. After an unhappy time, Grant stepped away, letting a triumphant Stanton return. Johnson still attempted to use Grant and also Sherman to get rid of Stanton—and he even succeeded in publicly humiliating Grant, who by this time was emerging as the likely Republican candidate for president in 1868.Advisors and his few remaining political friends urged Johnson to appoint someone who would at least be acceptable to Congress, but the president didn’t listen. In February 1868, Johnson named Gen. Lorenzo Thomas as interim secretary and ordered Stanton removed. Stanton refused, and on advice of Grant and Sherman, stayed pat. Thomas was arrested, soon let free, and Congress immediately instituted impeachment proceedings against Johnson for violating the Tenure of Office Act, which had recently been enacted.

Gleeful and grim at the same time, Johnson welcomed the coming battle. He retained some of the best legal minds of the age to serve as his counsels and prepared to fight impeachment. He believed—correctly, I think—that the Radicals had finally overplayed their hand. This is what Johnson had been waiting for. Unable to defeat them politically since early 1866, Johnson had had little choice except to push them to more extreme positions until they hoisted themselves on their own petard. And once they failed, Johnson would reap the victory.

So, for the first time in American history—and, we now know, not the last—a

president was tried in Congress for high crimes and misdemeanors. Articles of impeachment were drawn up and passed from the House. In actuality, the 11 charges against Johnson were thin, and ultimately centered on differences in politics, rough political language and attempted (but unsuccessful) violation of an act whose constitutionality was questionable.

president was tried in Congress for high crimes and misdemeanors. Articles of impeachment were drawn up and passed from the House. In actuality, the 11 charges against Johnson were thin, and ultimately centered on differences in politics, rough political language and attempted (but unsuccessful) violation of an act whose constitutionality was questionable.After a month and a half of deliberation before presiding judge Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, a final vote on article 11 was taken on May 16 and the rest on May 26. The votes were razor close—one vote!—but they were enough: not guilty. Enough Moderates in the Senate changed their mind and voted against impeachment.

Aftermath

Johnson had won, yet he had lost; the Radicals had lost—a deflated Stevens would soon die—yet they had in a sense won, too. Even though Johnson escaped removal, he was utterly finished in the North. When he tried to secure the Democratic nomination that summer, the Democrats virtually ignored him.

Had he not championed their causes? Had he not fought the Radicals more than anyone? Johnson cried. It was true, but Democrats had fought impeachment not for Johnson, but against the Republicans. They wanted nothing more to do with him. Instead, they selected the lackluster Horatio Seymour of New York to run against Grant. (Seymour made a respectable showing against the most popular man in the country, which speaks of the weakness of the Republicans in 1868 and of Grant as a candidate.)

Undeterred, though, Johnson continued to fight the Radicals until the very day he left office. One of his final acts was to grant full pardons to all ex-Confederates, including Jefferson Davis—whom he had previously vowed to hang.

Two more things merit mention:

Seward’s “folly”

As mentioned earlier, William Seward’s political career ended because he stuck so close to Johnson. But he scored a couple of significant diplomatic achievements during the unhappy late 60s, most notably buying Alaska from Russia.

Seward wound up purchasing the huge land to the North instead of negotiating fishing and trading agreements, because Russia no longer wanted Alaska. He bought it for a steal: about $7 million.

Radicals held up the treaty out of sheer spite; they didn’t want Johnson to get any credit for anything, but thanks to levelheaded action from Charles Sumner, the treaty as finally approved.

Rails West/Hancock’s War/Washita

With Democratic opposition virtually nil during the war, Lincoln and the Republican Congress authorized federal funds for the construction of a transcontinental railroad. No longer would this be

a political football; it was going to be built starting in Omaha in the East and from California in the West. Though funding of this and other railroads would later cause a scandal, the transcontinental railroad went ahead when the guns fell silent.

a political football; it was going to be built starting in Omaha in the East and from California in the West. Though funding of this and other railroads would later cause a scandal, the transcontinental railroad went ahead when the guns fell silent.Building the railroad was one of the factors that helped turn the nation’s focus westward after “the late unpleasantness;” the other was continued westward migration, which brought with it the inevitable clashes with Indians. In December 1866, a large party of Sioux ambushed and killed and mutilated 81 soldiers near Fort Kearney, Wyoming in the so-called Fetterman massacre.

Reprisals were called for, but Johnson actually called for peace on the plains. Grant wanted the corrupt Bureau of Indian Affairs transferred to the War Department (he would act quite differently when he was president, but had the same goal in mind) but Johnson demurred, instead preferring to investigate why these attacks and counterattacks kept happening. His commission reported that the best way to avoid clashes was—surprise—“do no injustice to them.” (Castle, p.123)

But Westerners wanted the Plains tribes tamed, so Missouri department commander Winfield Scott Hancock launched what became known in the press as Hancock’s War, a yearlong campaign in 1867 that provoked the tribes instead of overawing them. It culminated in the controversial battle/massacre of Washita (in present-day Oklahoma). George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Cavalry attacked the village of the Cheyenne Moketavato (Black Kettle) and killed mostly older men, women and children.

Regardless, Castle gives credit to Johnson for initiating the peace policy in the West, but Eastern reformers didn’t see it that way, and neither did Westerners. I tend to agree, for the real “peace policy” didn’t really begin until after Johnson’s successor took office.

Triumphant return

Andrew Johnson left the White House in March 1869 without accompanying Grant to his inaugural. Johnson had been defeated and rejected, but as always, he treated those as temporary. He would spend the next five years attempting to return to power in Tennessee politics.

Finally, Tennessee voters returned him to Washington as a Senator in 1874. He assumed his seat in 1875 and made one well-received speech on the floor against the Grant administration. Former enemies actually greeted him warmly, and with little wonder. By 1875, the country was tiring of “waving the bloody shirt” in support of black rights against the South, and some were beginning to remember the Johnson years a little fondly.

Johnson had actually recovered some of what he had lost as president, and lived long enough to have a last laugh over the increasingly unpopular Radicals before he died on July 31, 1875.

Final Assessment

I’m not of the mindset to label Andrew Johnson a failed president as Albert Castle does in his presidential analysis, nor do I agree with Eric Foner, the dean of modern Reconstruction historians, who argues that Johnson was a complete failure, because I don’t think he was that bad. Nor do I agree, of course, with the early 20th century Dunning School that claimed Johnson was “near great.”

He did a number of things right. For example, Johnson prevented Lincoln’s assassination from turning the surrenders into a rekindled war of revenge, and he took on the overreaching, imperial Congress over an unconstitutional law. Those two actions alone keep him from being labeled a failure.

However, he was mostly unsuccessful in his real goals: He failed to form a new party around himself; he failed to stop the Radicals’ reconstruction programs, and even pushed the Moderates and Radicals together instead of breaking them apart; he even failed to secure his party’s nomination. (If it would be fair to say that Johnson had a goal of keeping America a white man’s country, well, he was somewhat successful in that, at least for a while.)

My two primary sources conclude:

“…[I]t is clear that although the seventeenth president unquestionably undermined Reconstruction and left a legacy of racism, he was an able politician. Overcoming all opposition in his own Democratic party, he became a dominant force in it, while at the same time frustrating all efforts of the opposition. His courageous stand for Union also paid handsome political dividends, enabling him to reach the highest office in the land. What defeated him during his term in the White House was not so much his lack of formal education, nor even his tactlessness, but his failure to outgrow his Jeffersonian-Jacksonian background. … [H]is attachment to a strict construction of the Constitution that was no longer in vogue, his refusal to adjust racial views to the needs of the Republican party…blinded him to the realities of the post-Civil War United States. … [H]e failed to impress his contemporaries in the country at large, and his administration was a disaster. Johnson was a child of his times, but he failed to grow with it.” (Trefousse, pp.378-379)True, somewhat. But you can also say that about most of the South, except for Unionists and freed slaves. I agree more with Castle, who describes Johnson as a strong president, and writes:

“…[B]ecause of his blunders and obstinacy, the presidency in an institutional sense plummeted to it lowest point of power and prestige in its history… Finally, Johnson was far from being altogether wrong about Reconstruction, and the Republicans were far from being altogether right. Yet the dominant factor of his presidency is this: His policies were defeated, those of his enemies triumphed.” (Castle, p. 230)President Johnson was often simultaneously right and wrong: he could brilliantly oppose something on good, arguable constitutional grounds, but would sabotage himself either through his unguarded speech, obtuse myopia, ambition or even racism.

Likewise, history hasn’t made up its mind about Johnson. At first, historians denounced Johnson as an obstacle, then, by the turn of the century, as an incompetent. But by the 1920s, the “Dunning School” had reversed thinking and had elevated Johnson to “bear great” status for his defense of the Union and Constitution against the “evil” Radicals. His status was secure through the 1950s, but in the 1960s, a new generation of historians reversed course and threw Johnson aside as a backwards, hopeless racist. We’ve climbed a few notches up since then, but not much, and Johnson still remains near the bottom of the heap. Again, this does him a disservice. His racism should not be overlooked, but it alone cannot be allowed to define him, either, in this ultra politically correct age.

Resources

My primary resources were The Presidency of Andrew Johnson by Albert Castle (1979), part of the University of Kansas’ American Presidency series, and Andrew Johnson: A Biography, by Hans L. Trefousse (1989). Both authors were well respected in the field of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Also useful was the new book The Avenger Takes His Place: Andrew Johnson and the 45 Days That Changed the Nation by Howard Means (2006). (The title is pretentious and is typical of an unfortunate trend in history books lately where every event is treated as a "BIG thing" that changed American forever.)

For a useful (or amusing) exercise to see how thinking has changed on Andrew Johnson, read or skim the following: James Ford Rhodes’ History of the United States Since the Compromise of 1850, (volume 6) from 1906, which depicts Johnson as utterly “ill-fitted” for the work of Reconstruction; then read 1928’s The Tragic Era by Claude Bowers, a member of the Dunning school, which elevates Johnson to near-saint status. Then read W.E.B. DuBois’ Black Reconstruction in America, written in the 1930s as a response to the Dunning school. Then read Eric Foner’s definitive 1987 Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, which advances the line that Johnson was a hopeless racist.

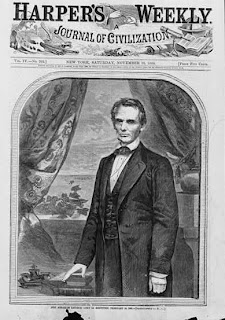

Illustrations

All illustrations are in the public domain and taken from the Library of Congress Photographs and Prints Division unless otherwise noted.

1. Matthew Brady took this portrait between 1855 and 1865.

2. Andrew Johnson had this portrait taken at A. Bogardus & Co. in New York.

3. Andrew Johnson takes the oath of office in the small parlor of the Kirkwood House Hotel on April 15, 1865, as depicted in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated.

4. Official White House portrait (White House Historical Association)

5. Thomas Nast drew And not this man? for Harper’s Weekly in August 1865. It depicts Lady Liberty presenting a crippled black Union Army veteran as someone deserving of the franchise and other rights. President Johnson was quite correct to continually deride the hypocrisy of imposing black political and civil rights on the South when they were denied in the North.

6. This 1866 Pennsylvania broadside presets the opposite view of Thomas Nast’s cartoons. It says: The Freedman’s Bureau! An agency to keep the Negro in idleness at the expense of the white man. Twice vetoed by the President, and made a lawy by Congress. Support Congress & you support the Negro Sustain the President & you protect the white man.

7. Full-length photo taken by Brady.

8. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated depicted Andrew Johnson as a woodsman taking two children, “civil rights” and the Freedman’s Bureau, into the “veto woods,” on May 12, 1866.

9. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania was the chief Radical “traitor” in the House, and the House manager of Johnson’s impeachment.

10 Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton posed for this portrait during the war. Johnson’s attempt to remove him from office to test the unconstitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act in the courts triggered his impeachment.

11. George T. Brown, sergeant-at-arms, serving the summons on President Johnson, sketched by T.R. Davis for the March 28, 1868, issue of Harper’s Weekly. The man to Johnson’s right is his faithful secretary, Col. W.G. Moore.

12. The Senate as a Court of Impeachment for the Trial of Andrew Johnson was published in Harper’s Weekly in April 11, 1868.

13. “This is a white man's government… We regard the Reconstruction Acts (so called) of Congress as usurpations, and unconstitutional, revolutionary, and void" - Democratic Platform. This Thomas Nast cartoon, published in the Sept. 5, 1868, Harper’s Weekly, illustrates the ultimate rejection of Andrew Johnson. It depicts a man with “CSA” (Confederate States of America) on his belt buckle holding a knife “the lost cause,” a stereotyped Irishman holding a club with “a vote,” and another man wearing a button with “5 Avenue” and holding a wallet with “capital for votes.” They stand on a black soldier sprawled on the ground. In the background, a “colored orphan asylum” and a “southern school” for freed slaves are in flames; black children have been lynched near the burning buildings. The cartoon is supposed to represent what the Democratic platform means for the South if the Republicans are defeated and Reconstruction is ended.